- Project Information

- Instructional Design

- Instructor Materials

- Assessments

- Available Topics

- Introduction to Forages

- Overview

- Pretest - Introduction

- Instructional Objectives

- Define forages and differentiate between forage types.

- Explain how forages have been and are essential to civilization.

- Summarize the history of forages.

- Define grassland agriculture. Discuss a typical grassland ecosystem.

- Define sustainable agriculture and discuss how forages are a key component.

- List several grassland organizations and describe their role in promoting forages and grassland agriculture.

- Summary

- Exam

- References

- Grasslands of the World

- Overview

- Pretest - World Grasslands

- Instructional Objectives

- Define and describe the natural grasslands of the world.

- Locate and describe the tropical grasslands and their forages.

- Locate and describe the temperate grasslands and their forages.

- Important issues affecting grasslands and their forages.

- Summary

- Exam

- References

- Forages in the US

- Overview

- Pretest - U.S. Grasslands

- Instructional Objectives

- Describe the role of forages in the history of the US.

- Describe the current role of forages in US agriculture.

- Discuss regional forage production.

- Discuss forages from a livestock perspective.

- Discuss the environmental benefits of forages.

- Discuss the possible future role of forages in the US.

- Summary

- Exam

- References

- Grasses

- Overview

- Pretest - Grasses

- Instructional Objectives

- Grasses are very common but very important.

- Differentiate warm-season from cool-season grasses.

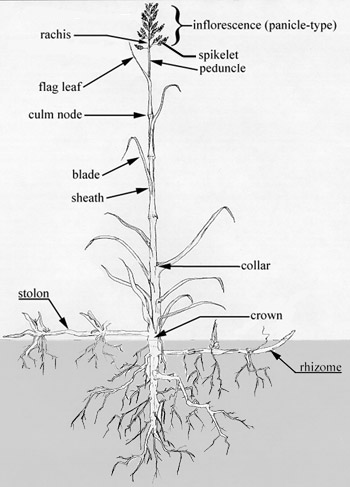

- Summarize the distinctive physical characteristics of grasses

- Describe the utilization of grass in forage-livestock systems.

- Describe how knowledge of grass regrowth is beneficial to forage managers.

- Provide specific information about the common grasses used as forage

- Summary

- Exam

- References

- Legumes

- Overview

- Pretest - Legumes

- Instructional Objectives

- Legumes are a valuable part of forage production.

- Differentiate warm-season from cool-season legumes.

- Summarize the distinctive physical characteristics of legumes.

- Define the utilization of legumes in forage-livestock systems.

- Provide specific information about the common legumes used as forage.

- Summary

- Exam

- References

- Plant Identification

- Overview

- Pretest - Plant Identification

- Instructional Objectives

- Explain the reasons why forage plant identification is important.

- Describe the major differences between the plant families used as forages.

- Provide the vocabulary needed to identify grasses.

- Provide the basic vocabulary for identifying legumes.

- Identify common species of forage.

- Provide practice in identifying common forages.

- Summary

- References

- Forage Selection

- Overview

- Pretest - Forage Selection

- Instructional Objectives

- The selection of a forage plant is crucial.

- Determine limitations to forage selection.

- Forage selection requires an understanding of species and cultivars.

- Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of selecting mixtures.

- A model for forage selection

- Summary

- Exam

- References

- Establishment

- Overview

- Pre-Test

- Instructional Objectives

- Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of pasture establishment

- Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of pasture renovation.

- Discuss the steps in seedbed preparation.

- Discuss the considerations of seed quality.

- Discuss the methods and timing of seeding.

- Discuss the purpose and wise utilization of companion crops.

- Summary

- Exam

- References

- Weeds

- Overview

- Pre-Test

- Define the term weed.

- Instructional Objectives

- Explain why producers and the public should be concerned about weeds.

- Describe several ways in which weeds cause forage crop and animal production losses.

- Describe methods in determining quality

- List several poisonous plants found on croplands, pasturelands, rangelands, and forests.

- Describe the five general categories of weed control methods.

- Describe the concept of Integrated Pest Management and how it applies to weed control.

- Distinguish between selective and non-selective herbicides and give an example of each.

- Describe how weeds are categorized by life cycle and how this is correlated with specific control methods.

- Describe conditions that tend to favor weed problems in pastures and describe how to alleviate these conditions.

- Describe several common weed control practices in alfalfa production.

- List printed and electronic sources of weed control information.

- List local, regional, and national sources of weed control information.

- Summary

- Exam

- References

- Management/Physiology

- Overview

- Pre-Test

- Instructional Objectives

- Discuss the basics of grass growth.

- Describe the impact of defoliation on grass plants.

- Discuss how grasses regrow.

- Discuss how livestock interaction impacts grass growth.

- Discuss grass growth in mixed stands.

- Discuss the practical applications of regrowth mechanisms.

- References

- Fertilization

- Overview

- Pre-Test

- Instructional Objectives

- Discuss the importance of soil fertility and the appropriate use of fertilization.

- Define and discuss the nitrogen cycle.

- Discuss the major elements needed for good soil fertility and plant growth.

- Define and discuss micronutrients.

- Discuss the uses and methods of liming.

- Discuss fertilizer management for mixed stands.

- References

- Biological Nitrogen Fixation

- Overview

- Pre-Test

- Instructional Objectives

- Define biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) and explain its importance.

- Describe the benefits of BNF in economic and environmental terms.

- Estimate the amount of BNF that is contributed by various crops.

- List and discuss factors that affect the quantity of nitrogen fixed.

- Describe the processes of infection and nodulation in forage legumes.

- Describe the process of inoculation in the production of forage legumes.

- Summary

- Exam

- Grazing

- Overview

- Pre-Test

- Instructional Objectives

- Discuss the role of grazing in a pasture-livestock system.

- List and discuss the types of grazing.

- Compare and contrast the different types of grazing.

- Discuss the livestock dynamics on pastures and grazing.

- Discuss the utilization of a yearly grazing calendar.

- Summary

- References

- Mechanically Harvested Forages

- Overview

- Pre-Test

- Instructional Objectives

- Discuss the purpose for mechanically harvested forages.

- List the characteristics of good hay and the steps needed to make it.

- Determine the characteristics of good silage and the steps in producing it.

- Discuss the potential dangers in mechanically harvesting and storing forages.

- Compare and contrast the types of storage and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each.

- Summary

- References

- Irrigation

- Overview

- Pre-Test

- Instructional Objectives

- Describe the importance of irrigation in producing forages.

- Describe major types of irrigation systems in US forage production.

- List and discuss factors that affect irrigation efficiency.

- Describe basic principles of scheduling irrigation for efficient use of water resources.

- Describe potential problems that may arise from the use of irrigation in forages.

- Summary

- References

- Quality & Testing

- Overview

- Pre-Test

- Instructional Objectives

- Define forage quality and management decisions that increase forage quality.

- Describe important factors that determine hay and silage quality.

- Discuss components of forage

- Define and discuss antiquality factors affecting animal health

- Discuss the need for and progress towards standards in national forage testing

- Summary

- References

- Breeding

- Overview

- Pre-Test

- Instructional Objectives

- Discuss the history of forage breeding in the United States

- Discuss the philosophy of why new plant cultivars are needed

- Discuss the objectives of forage plant breeding

- Discuss the process of creating a new cultivar

- Discuss the steps in maintaining and producing new cultivars

- Compare and contrast plant breeding in the US and Europe

- Summary

- References

- Forage-livestock Systems

- Overview

- Pre-Test

- Define a livestock system and their importance

- Describe the basic principles of a successful forage-livestock system

- Discuss forage-livestock systems in a larger picture

- Discuss how economics are a part of a forage-livestock system

- Discuss the types of forage-livestock systems

- Summary

- References

- Miscellaneous Forages

- Overview

- Pre-Test

- Instructional Objectives

- Discuss the importance of utilizing forages other than common grasses and legumes

- Discuss the species suitable to use as miscellaneous forages

- Compare and contrast the species suitable to use as miscellaneous forages

- Discuss the utilization of crop residues in a forage-livestock system

- Discuss the utilization of a yearly grazing calendar

- Summary

- Exam

- References

- Economics of Forages

- Environmental Issues of Forages

- Overview

- Pre-Test

- Instructional Objectives

- Describe several important environmental issues that relate to forage production

- Define the terms renewable resource and nonrenewable and give examples of each resource type that are related to forage production

- Define the term sustainable agriculture and apply the concept to forage production

- Diagram and describe a sustainable forage production system

- Discuss factors that contribute to soil erosion and discuss ways that soil erosion control can be integrated into forage product

- Discuss advantages and disadvantages in using synthetic agrichemicals in forage production

- Explain the concept of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) and how it can be used to enhance sustainable forage production

- Define the term biodiversity and explain how this concept could be applied to forage production

- Discuss the controversy over using agricultural land to produce crops for animal consumption

- Summary

- References

- Introduction to Forages

- Instructor Feedback

- Laboratory Strategies

- Lecture Strategies

- Mailing Groups

- Student Materials

- Reference Materials