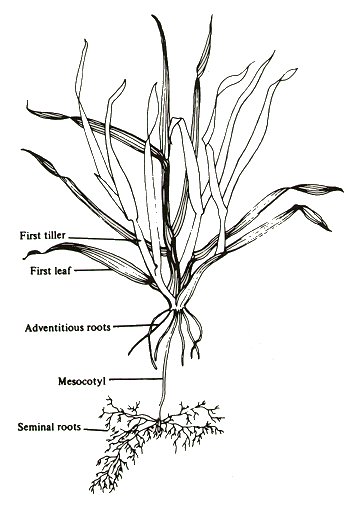

Tillers are very important to understanding grass growth and regrowth. Unfortunately the term has many synonyms and is sometimes confusing. Tillers are new grass shoots, made up of successive segments called phytomers, which are composed of a growing point (apical meristem which may turn into a seed head), a stem, leaves, roots nodes, and latent buds; all of which can rise from crown tissue buds, rhizomes, stolons, or above ground nodes (aerial tillers).

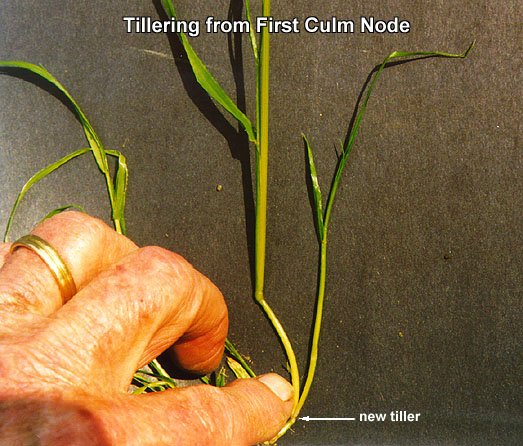

A tiller may become induced to flower if exposed to necessary growing conditions, otherwise it will remain vegetative. The process by which these new aerial shoots emerge is called tillering. In contrast to rhizome and stolon emergence, tillers develop upwards. The result is a dramatic increase in the number of new shoots occurring immediately adjacent to the original shoot. The original shoot is sometimes referred to as the "parent plant" while the new tillers are termed "daughter plants." Chapman (1998) defined a tiller as a subsidiary culm arising at or near the base of the primary culm, or one of its earlier subsidiaries."

A single kernel of wheat may produce additional shoots (tillers) from adventitious buds in the crown zone. Corn (maize), a warm-season annual grass, produces suckers from basal nodes. With perennial grasses, some species produce tillers from adventitious buds in a manner similar to maize. If the shoot initial remains within the sheath that envelops the node, the branching is classified as intravaginal. Examples are orchardgrass, fescues, and other bunchgrasses. If the intravaginal shoot arises higher up on the culm (second or third node from the crown) the new shoot is considered to be an aerial branch, as with annual ryegrass. More of this information is found in the summer annuals section.

If the shoot initial grows laterally in a manner which ruptures the enveloping sheath, the branching habit is extravaginal. The latter classification includes rhizomatous and stoloniferous grasses. If the rhizomes are short, as with side-oats grama, the grass will not be invasive to companion species.

Tillering may also refer to the growth stage when the shoots emerge. With cereal grains, tillering in early spring is called "stooling." Each new shoot contains a central growing point (shoot primordium) which eventually develops into a jointed stem, characterized by distinct nodes and internodes as found on a bamboo pole. The jointed stem is called the culm. Each node of the culm bears a leaf (a blade and sheath). The uppermost culm segment supporting the seed head is called the peduncle.

In a forage planting, individual shoots eventually die and must be replaced by new shoots to maintain a desired density of plants. Forage perennial grasses are perennial not because individual shoots survive indefinitely, but because the plant community is dynamic, with dying members continually replaced by new shoots. The life of an individual shoot is usually not more than one year, and frequently less. Tillers formed in the fall are important to winter survival of the stand and spring regrowth, but may die during summer. Tillers formed in the spring may be important for summer survival. Those tillers initiating inflorescences in spring usually die before the end of summer.

A young tiller depends on the parent shoot for photo-assimilates until it has developed several leaves and an adequate root system. Although a mature tiller may appear to function as an independent entity, some relationship apparently exists between tillers interconnected by a common vascular system. Thus, a grass plant appears to be a highly organized system rather than a collection of competing tillers.

Tillering provides for better establishment of bunch grasses, and for lateral spreading (via rhizomes/stolons) of sod-forming grasses. Tillers produce many additional roots. Therefore, grazing should be deferred in the spring until such time as they can tolerate limited defoliation.

1) Species that have an extensive tillering habit may be planted at lower seeding rates.

2) With certain management precautions, early grazing does not pose a serious threat to the livestock manager. For example, midwestern and southern wheat farmers commonly graze early growth of wheat during the tillering phase of development. However, when the shoots start to produce a central stem (early-jointing or transition stage) they cease grazing because of the possible destruction of the growing point which contains the rudimentary seed head. Similarly, in western Oregon, sheep are commonly put on grass seed fields to graze but are removed before culm elongation. But, there is an additional threat at this growth stage. Livestock might defoliate a shoot in a manner which saves the growing point but may cause one or more leaf blades to be defoliated below the collar zone. When this occurs, the recovery growth consists of a flowering stem with the seed head in tact, but with severly reduced leaf blade area. Leaves are the site of photosynthesis, so livestock should not graze so long that plants are denuded.

The above response to early grazing is commonly seen with rotational grazing where several paddocks are grazed sequentially. The first paddock is frequently grazed for too long resulting in recovery growth comprised chiefly of skeletonized flowering stem (a naked culm with a seed head but no leaf blades). The pasture should be clipped to destroy the seed heads and remove apical dominence which will allow basal buds to develop, essentially directing plant energies to regrowth.

If livestock are permitted to graze the 2nd paddock too intensively, the above-ground regrowth mechanism may be totally destroyed. If this effect coincides with a brief period when adventitious buds in the crown are poorly developed and incapable of producing new tillers, weeds and legumes will flourish.

Continuing the above sequence of grazing events, padock #3 would be grazed during the grand growth phase (late or early-boot stage). The grass is near the peak of both quality and quantity. If the stocking rate is not increased in order to maximize profits from this resource, many of the grass tillers (shoots) will produce seed heads rendering the forage unpalatable. Such pastures should be clipped at seed head emergence. This triggers early regrowth, providing the opportunity for the second cycle of tillers to produce a new root system prior to midsummer heat and drought stress.